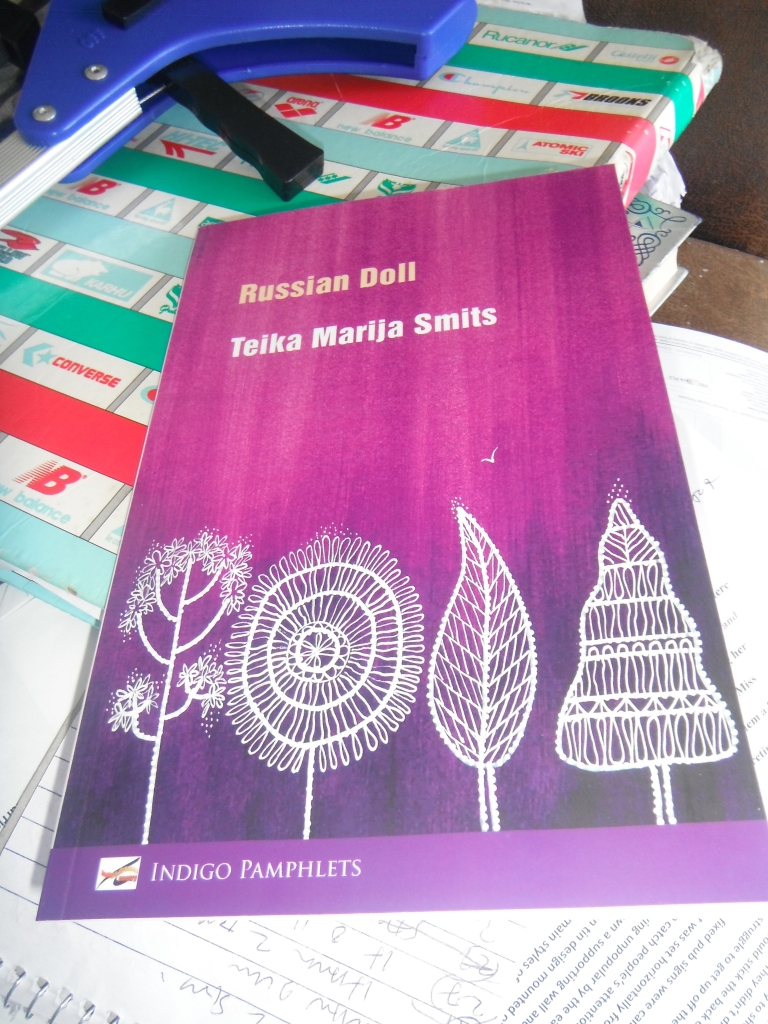

Teika Marija Smits is writer and editor with an extraordinary range and diversity. Her resume includes science fiction, fantasy and studies in motherhood. This is the first of hopefully many collections of her poetry.

It’s a slender volume with just twenty-one poems, but as rich and vibrant as a novel.

There is a chronology to the poems, giving a sense of autobiography that gives the verse a deep sense of honesty and the deeply personal.

The narrator goes from describing the escapology skills with which she clamboured from her cot to join her parents in their bed, through a delicious description of a Choc Chip ice cream laid out in the shape of an ice cream cornet.

The text gets more serious in Teika’s description of her athletic, and competitive friend Anne Marie, always ahead in life, only to succumb to depression and suicide despiye having seemed so much better in every way. This is slammed home harder later when, after watching Inner Space (about a shrinking people to put them inside other people) she and her father discuss the scientific and medical applications of the idea, oblivious that her father was already dying and beyond such help. I could really relate to this, as during my own bowel cancer crisis in 2020, I found myself thinking a lot about an earlier film on the same premise, Fantastic Voyage, in which surgery is performed on a patient by miniaturized surgeons.

Her father’s death during a routine shopping trip comes in the very next poem, and again it strikes personal chords, as my father died alone in a city centre cafe in Manchester aged 49, in 1978 from coronary thrombosis. It felt like the death of my childhood, and my cancer almost repeated his fate on me at a time when Covid made it impossible for anyone to visit me.

The Russian Doll title refers to the Russian souvenir dolls within dolls you can buy (I got my Gran one on a childhood visit to ‘Leningrad’ as it was ten known, in 1977). Here it is a metaphor for the complex inner selves we have, the youth within the more mature self, the inner grief, creativity, etc.

In the second half of the collection Teika goes from being the daughter doll in the family to being the mother figure, the outer, more protective shell to her own inner dolls as much as mother to her own family.

During pregnancy Teika went through phases of seeing her child as some kind of cursed fairie entity changeling in possession of her belly but came to love and understand her through support from the father and medication.

I really like ‘The Right Tool’ piece, in which Teika is impressed by her son’s pragmatic sense of what instruments and tools are needed for various tasks, given that her grandmother somehow achieved everything with the same knife. Teika is frightened by a Warcraft computer game involving zombies where her son is able to fend them off easily while she wants only to scream and flee. Here is a sense of changing perspectives over generational divides.

The title poem indicates the regrets that come of age, as the author feels her younger selves, her inner dolls, might be disappointed with the outer layer, but the closing verse shows greater optimism, as Teika takes to a swing, remembering doing so as a child, feeling renewed, reinvented, reborn.

Of course, her immense talents show just how much Teika still has to give, take and share in life. This is a wonderful collection. Her admission to her sense of her vulnerabilities and frailties are actually showing how strong and powerful she really is.

Arthur Chappell.