Poem My Longest Day

Written to commemorate the 6th June 2024 80th Anniversary of the Normandy Landings.

Like shells bombing down on the beaches

A deadly bombshell reaches

Across time from Forty-Four to Seventy Eight

To the anniversary of the famous Normandy landing date

A message sent me home on unexpected leave

Unaware of the tragedy that I would soon begin to grieve.

All I was told was that my Dad had been taken ill.

The class sounded silent, and time seemed to stand very still.

I got home to find he wasn’t ill, but dead

My own D-Day, when the D Word was not being said

As though breaking it to me gently would spare me some of the pain

But I said he was dead and begged the rest of the family explain

What had happened, trying to take stock

Already reeling in a state of shock.

My dad had been out alone having breakfast at his favourite café in Town

When he clutched at his chest as if shot, and instantly fell down

A blood clot bullet had slammed into his heart.

Mouth to mouth resuscitation had failed to restart

Him, so like the families of those who fell at Normandy

News of his fall struck like shellshock on me and the rest of the family.

I grew up that day. My childhood died with my Dad

I didn’t just end up feeling terribly sad

I was spiralling into full on depression and despair

Told that I was the man of the house now, and that I had to care

For everyone I just wanted to desert and run, like a coward under fire

I left school too stressed and agitated, so no employer would hire

Me, and like many returning soldiers, I was unemployed.

Books, beer and self-loathing were the only things I enjoyed.

I had no medals, no glorious heroics to my name

I felt useless and as if I’d brought my family nothing but shame.

In consequence and as a result

I retreated into a mysticism cult,

Blindly following the orders of a self-appointed messiah

Many former friends saw me as a social pariah.

My guru gave orders I followed without question

Totally brainwashed, open to suggestion

Like the Nazis who thought Hitler the source of their salvation

Until I came to my senses and achieved my own liberation.

Would Dad have hated me for joining the cult in the first place?

Instead of helping my family I was a selfish disgrace

Or would he be proud of how I broke myself free?

Writing my verse, gaining my academic degree.

My Dad was born just too late to sign up and fight in the war

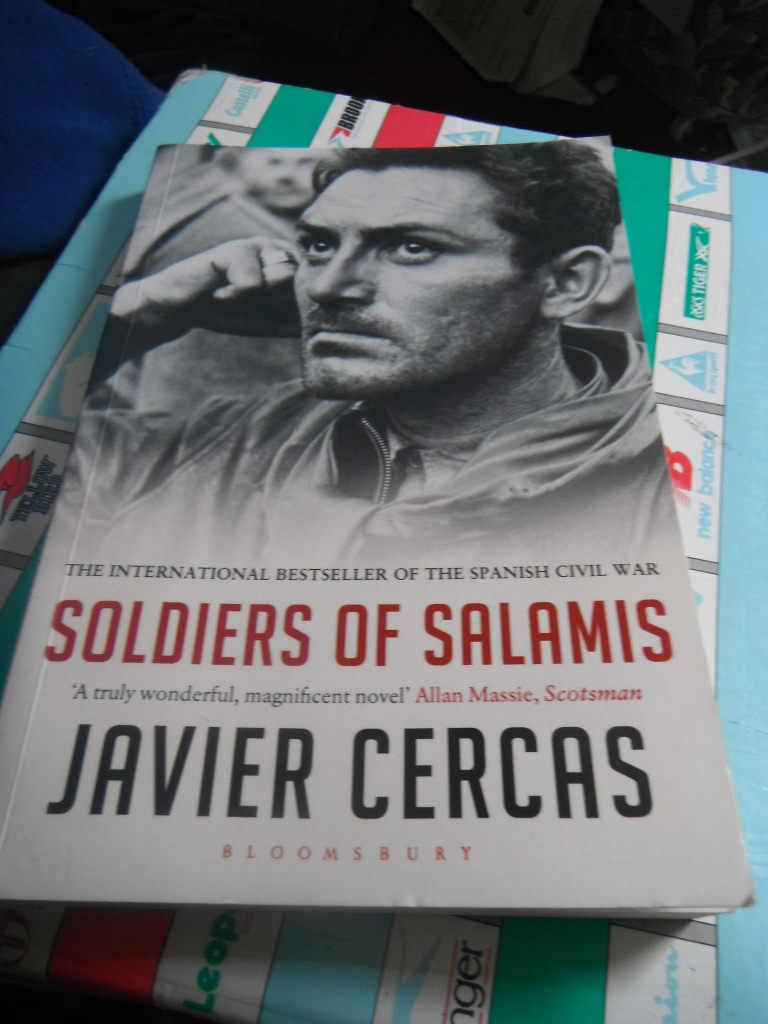

He wished he had gone and read every war book he ever saw

But he remains my hero, cruelly taken away

On the thirty-fourth anniversary of D Day.

Now, eighty years on, we remember again

The many brave men who fought to obtain

Freedom and liberty, ending Fascist and Nazi tyranny.

Many fathers and sons fell to guns and mines every step of the way.

Let’s never forget to salute their bravery on 1944’s more famous D-Day.

Photos taken by me.

Arthur Chappell